Wild Secrets: Prado’s Little Dam

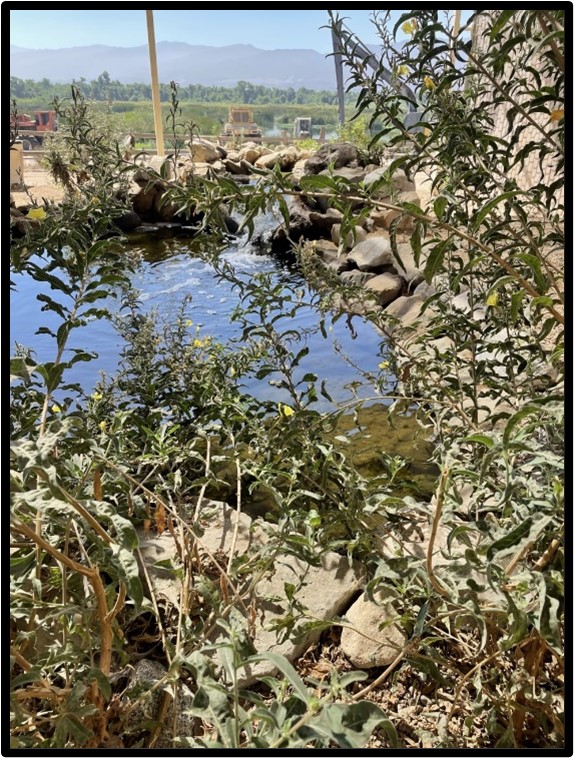

The shaded pool with its bubbling cascade on the Prado office veranda is a place for tranquil reflection; well, unless it is 110 degrees out with Santa Ana winds blowing over 50 miles per hour. The pond is small compared to the wetland ponds, but large enough to carry ripples from the falls to a quiet pool that reflects the sky beyond, readily whisking one away to adventures on other waters.

For me, those are memories of mountain trout streams and lakes, explorations, wild traverses, and prize fishes. Here and now, there are welcoming benches, picnic tables, a tribute etched in stone commemorating two champions, Loren Roy Hays and Dharm Vireo Pellegrini of OCWD’s nationally acclaimed endangered vireo monitoring program, a few native plants, and aquatic life including fish.

Arroyo Chubs

Arroyo chubs are native minnows that thrive in the Prado yard stream, along with many other creatures. The chub were transplanted from the river to explore the efficacy of our small, native fishes for mosquito control in lieu of the non-native mosquito fish. Arroyo chubs (Gila orcutti) are small, chunky fish; gray-olive green backed with white underside; large eyed, small mouthed; exceptionally five inches long, typically three – three-and-a-half inches; consumers of algae, small insects, and other invertebrates harbored on aquatic plants or pool bottom; and spawning in spring to early summer, sometimes repeating later in the year. Chubs survive low oxygen, fluctuating stream levels and temperatures, well adapted to ephemeral Southern California stream conditions. In the past, we have found chubs in the river below River Road, near the diversion to the Prado Wetlands. Arroyo chubs will scatter when you approach the pool, darting for bottom cover. If you remain still, observant, they quickly reemerge to go about their fishy business. They are curious enough to be easily captured in a pole net patiently deployed. Placing the net on the bottom scatters them but they soon are out exploring this new object; quick, adept retrieval brings in those fish that ventured into the net’s inner folds.

Mosquitofish

Our chubs could be used in lieu of mosquitofish which are small, green-grey fish that were imported from the southern midwest by vector control agencies to eat mosquito larvae. Mosquitofish are half the size of chub; males are smaller than females that measure up to 2.5 inches. Their mouths are terminal, facing upward, for eating prey at the water’s surface. Thus, they school in the calm shallows, near the banks, rarely in swifter flows. Mosquitofish tolerate variable water conditions, including ponded water with low dissolved oxygen levels. They are highly fecund; females give birth to as many as 300 young and store sperm after the initial spawn to reproduce again without further need of a male. Mosquitofish are aggressive omnivores that feed on almost anything, competing with native fish for food and even consuming native fish eggs, larvae, and juveniles. Although smaller, they will displace native fish and even attack other fish, shredding fins, and sometimes killing them. Mosquitofish help with mosquito control but hinder native fish conservation but our natives could be controlling pesky flies just as well. Mosquitofish abound in most Southern California waters today, but not in our little pond.

Native minnows are abundant and obvious in the pond but so are many other creatures. You might see water striders skating the surface; water boatmen breast-stroking for surface air with elongated hindlegs; a giant water beetle, also dubbed toe-biter scurrying along the bottom; or a black phoebe bill-snapping as it sallies after flying insects.

Western Toad

Under water or cover is the western toad, a common predator of smaller animals that is found throughout the Prado Basin. These are large toads, four-to-five inches in length, squatty with dry, warty skin, and horizontal pupils. They are reddish-brown, to gray, and olive green on top often with darker spots and blotches and a cream-colored stripe down the middle of the back. The underside is yellow, or cream colored with dark blotches. The tadpoles are dark in color, they aggregate in knots and eat plant material and detritus. Adults feed on flying insects, spiders, crayfish, and earthworms and are distinct from other frogs and toads in that they typically walk rather than hop. When these toads are threatened, they excrete a mild white poison from their parotoid glands (oval bulge behind each eye) and warts. They are mostly nocturnal, burrowing into soil, woody debris, or sequestered in abandoned burrows by day. Females deposit eggs on aquatic plants in two parallel stringers of 12,000 or more eggs and unlike other toads and frogs, males don’t utter a loud, beckoning, mating call in spring.

Under water or cover is the western toad, a common predator of smaller animals that is found throughout the Prado Basin. These are large toads, four-to-five inches in length, squatty with dry, warty skin, and horizontal pupils. They are reddish-brown, to gray, and olive green on top often with darker spots and blotches and a cream-colored stripe down the middle of the back. The underside is yellow, or cream colored with dark blotches. The tadpoles are dark in color, they aggregate in knots and eat plant material and detritus. Adults feed on flying insects, spiders, crayfish, and earthworms and are distinct from other frogs and toads in that they typically walk rather than hop. When these toads are threatened, they excrete a mild white poison from their parotoid glands (oval bulge behind each eye) and warts. They are mostly nocturnal, burrowing into soil, woody debris, or sequestered in abandoned burrows by day. Females deposit eggs on aquatic plants in two parallel stringers of 12,000 or more eggs and unlike other toads and frogs, males don’t utter a loud, beckoning, mating call in spring.

Tree Frogs

Up close, you can hear the soft call of the western toad, but in the evening, you are more likely to catch the loud, constant cricket-like sound of the tree frog. The crescendo of calls waxes and wanes with the competing night sounds, perceived threats to the tiny croakers. As you walk by a wetland pond, the nearest frogs cease calling whereas those further off persist, audibly tracking the progress of your evening stroll. Where there are emergent cattails, bullrushes, or other tall, shoreline plants for them to clamber out of harm’s way with their suction-cupped toes, tree frogs abound. These small, one-to-two inches, masked beauties have done better than most native amphibians in surviving the onslaught of invasive predators and competitors that dominate our streams, lakes, and rivers today.

Up close, you can hear the soft call of the western toad, but in the evening, you are more likely to catch the loud, constant cricket-like sound of the tree frog. The crescendo of calls waxes and wanes with the competing night sounds, perceived threats to the tiny croakers. As you walk by a wetland pond, the nearest frogs cease calling whereas those further off persist, audibly tracking the progress of your evening stroll. Where there are emergent cattails, bullrushes, or other tall, shoreline plants for them to clamber out of harm’s way with their suction-cupped toes, tree frogs abound. These small, one-to-two inches, masked beauties have done better than most native amphibians in surviving the onslaught of invasive predators and competitors that dominate our streams, lakes, and rivers today.

Aquatic Invaders

American bullfrogs and red swamp crayfish are two of the worst invaders, imported into California in the early 1900s with voracious appetites. They eat and outcompete everything. Along with imported fish like largemouth bass, native aquatic species are devoured in the smaller, most vulnerable life stages but even adults of smaller species like chub are taken. The once most abundant native frog in Southern California, the California red-legged frog, Mark Twain’s Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County is gone from our watershed and all but gone elsewhere in the state because of these dominant invaders.

Although the success of non-native aquatic species has imperiled many natives, the invaders are consumed in quantity by native predators of all sizes. You never know what might show up next in the Prado yard pool, but I will tell you this – our Natural Resources team enjoys every moment of it. Until next time!